In VR, Would a Rose Smell Sweeter?

In a few months, the first iteration of modern consumer virtual reality headsets are going to start shipping. A lot is rapidly changing and new applications are being discovered every week.

I present three stories that use VR technology to push our crafts beyond what was possible. Each story is focused around an amazing short video that is very much worth watching.

“This is not why I became an actor.”

On the set of The Hobbit, Sir Ian McKellen broke down in tears after hours of delivering his lines as Gandalf to a handful of photographs floating amidst a sea of green.

In an interview with Contact Music, he recalled:

In order to shoot the dwarves and a large Gandalf, we couldn’t be in the same set. All I had for company was 13 photographs of the dwarves on top of stands with little lights — whoever’s talking flashes up.> Pretending you’re with 13 other people when you’re on your own, it stretches your technical ability to the absolute limits.> I cried, actually. I cried. Then I said out loud, ‘This is not why I became an actor’. Unfortunately the microphone was on and the whole studio heard.

Today, we’re entering a different world. One where actors can be immersed in the virtual world they’re depicting as they’re depicting it.

Cloudhead Games is working with actor Adrian Hough to record the motion captured acting end-to-end for the first episode of The Gallery, right inside the world itself as it’s being acted out:

As Valve’s Lighthouse Tracking system becomes available later this year, trackable peripherals and body attachments will bring a world of consumer motion capture. Someday, it might even be the default for most VR experiences. You’ll raise your hand, wiggle your fingers, and take that precious swing to feel haptics sharply vibrate in your palm as you slap your friend across the continent. The future is here.

“What is this amazing new world?”

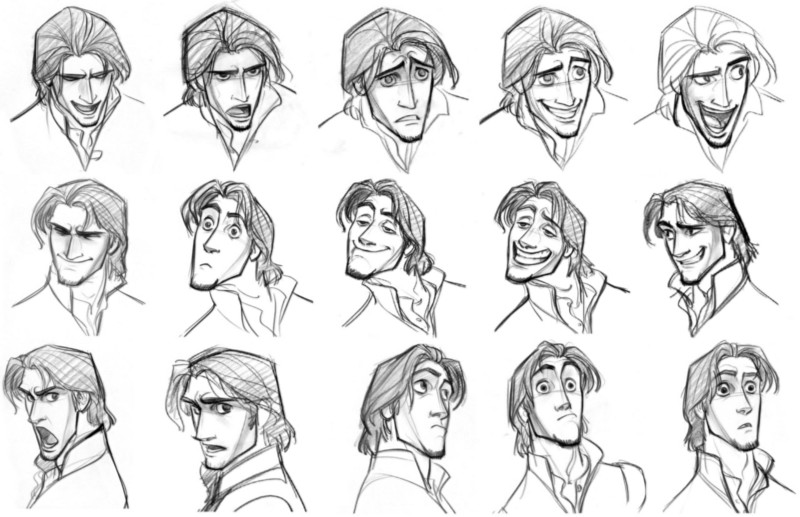

Glen Keane is an animator who worked at Disney for 38 years, he helped create many of the characters we all take for granted from our childhood.

Glenn Keane illustrations

In collaboration with the Future of StoryTelling Summit, Keane put on an HTC Vive headset and picked up the wireless controllers. He entered a new world:

When I draw in virtual reality, I draw all the characters in real life size. They are that size in my imagination.

This world is called Tilt Brush, a VR painting application created by Google.

For years we’ve been fed images of architects and surgeons using virtual or augmented reality to feel what it’s like to be inside their building or patient. But what about us? What about our inner child unleashed inside a life-sized world of our own design, not just staring at it from the distant abstraction of a flat display.

“Your crappy PC is the biggest barrier to [VR] adoption.”

Palmer Luckey, founder of now-Facebook’s Oculus RV, hosted a marathon of an IAMA on /r/pcmasterrace last week. One recurring topic was the recommended hardware requirements for running the Oculus Rift, specifically the “NVIDIA GTX 970 / AMD 290 equivalent or greater” — a $350 investment just for the video card, or more if you’re shooting for above the bare minimum.

In modern gaming, 1080p resolution is considered passable. At 1920x1080, these 2,073,600 pixels are what you’d expect on a PS4 or XBox 360 rendered about 30 times each second. On a PC, it’s common to see higher resolutions pushing 60fps. What happens if some big explosions break out and the frame-rate drops to 45? Not much. If it drops below 20fps, you might notice and grumble a bit until things calm down again.

The first iteration of VR is going to be a more expensive beast: Two camera positions need to be rendered for every frame—one for each eye—90 times per second. Not to mention that the display panels are higher resolution, probably around 1512x1680 per eye or 5,080,320 pixels total. And what happens if you swing your head and the frame-rate drops to 40 fps for a few moments? Nausea. You’re done.

Today, we’re talking about 62 million pixels/sec rendered on latest-generation consoles compared to at least 378 million pixels/sec rendered for nausea-free VR.

Sounds gloomy, but don’t fret—the forecast is sunny: If we can track where our eyes are looking at inside of the headset, we can reduce the full-quality rendering to less than a quarter of the resolution. This is called Foveated Rendering, and a German startup already has a working prototype:

What does this mean?

Once Foveated Rendering reaches consumers, we might actually see higher graphics quality and lower hardware requirements from VR than traditional flat-display technology.

I can’t wait.